In A World of Birds

Israt Jahan

ROBERTA SPICERTHE FLOCK of eleven geese (or more, I never counted) are blocking my path to class again. They always do this at 8:30 in the morning, as if they’re following the clock on my phone that I’m glued to as I walk between them. Either that, or that’s when the pond water is the warmest. But if it’s warm, why not just swim in it instead of walking along the concrete pooping green everywhere they go?

I hate geese with a passion. I hate their big, brown, feathered bodies the shape of a football I want to chuck. I hate their long, black necks that can missile strike a person if they so chose. I hate how they don’t give a shit about other people, and would go as far as to hiss at you if you give them even one bad look. Yes, they hiss. They hiss, revealing rows of sharp teeth in their beaks. I know this because I had to fight one when giving a campus cat food (yes, there are cats on campus). They kept trying to steal poor Jaden’s food, and I wasn’t having it.

It’s a wonder why I chose to focus on the geese today. I suppose it’s because they’re one of the most frequent visitors on campus and I can’t help but look at them as I weave my way between each of them just to get to the library. It’s hard to believe they’re not scared of humans despite us being the apex predators of the world. We can easily grab them by the necks and devour them, and yet they don’t care. Or geese don’t think we have it in us, with the way they sit in front of the paths and stare as if they own the place. I wonder what it’s like to not care about anything but yourself, your survival. Do they even care to survive? It’s almost winter and they’re still in the cold depths of New York weather. Granted, the forecast says it’ll be 78 degrees Fahrenheit this weekend, so I suppose their bodies have clocked that it’s summer instead of autumn despite the leaves on the campus trees changing color. Has climate changing affected the way their bodies react to normal environmental cues, stopping their hormones from acting despite the changing season? Is that why they choose to stay at the pond, because it’s supposedly still warm enough for them to inhabit? Or are they just stuck here because their large, brown bodies haven't told them to move yet? No time to sympathize with the geese. I have to get to class before one of them attacks me.

~~

Two blue jays hop along the fallen yellow leaves in front of the Engineering buildings. They’re not necessarily looking for food, although the fallen acorns are of some interest. Not as much as it is for the squirrel, who is also scouring in between the bushel of leaves that have yet to be cleaned up. I remember when the blue jays first came to campus this year in the Spring, when there were just flocks of them in the trees, chirping up a storm every morning. Now there’s fewer of them, or at least the two I see as I walk from class to my dorm. It’s not cold enough for them to migrate, given that it’s 70 degrees in the middle of October, but blue jays don’t really have a strict pattern for migrating. So do they just sense when to leave? Whenever they feel like it? Is that their way of freedom, choosing to leave when they can? Or is it a prison, waiting for your instincts to kick in to let them fly?

I don’t know, but right now, the blue jays seem content hopping the ground alongside the squirrel.

~~

It’s finally warm out after a hard winter, a nice 70 degrees. A lone, black bird-duck looking creature sits in the middle of the pond. It’s relaxing for a moment as two geese fight each other at the pond shore (not an important detail, but I feel like it needs to be said).

Sheen and I sit on one end of the pond shore, on the muddy grass, while another group of friends sits on the opposite side on a bench. All of us watch as the bird swims back and forth between little waves. The black bird, with hints of white and orange on its beak, glides along the pond in circles, occasionally dipping its face into the water and pulling out a fish from the algae-filled green path. Sheen and I didn’t know fish that big existed in the pond. We didn’t know how the bird itself knew, but it did, somehow, know this pond was filled with food and onlookers. We think he was much more intrigued with the onlookers.

Occasionally, he would flap his wide wings, revealing large, midnight feathers that could reflect stars if they really wanted to. Us onlookers would gasp in awe as he did, and he knew it. He knew he was putting on a show as he continued to spread his wings in an elegant motion, the pitch black feathers a striking contrast to the green grass and pond. He lifted himself off the water after a while, soaring in an infinity sign above the pond as he picked up momentum to reach the sky. He took his time, as if he was prolonging his departure for his audience all the more. As if telling us he’ll miss us before he reaches the blue sky, where he will inevitably forget us. Where he grabbed onto the current of the wind and flew off. Where he spread those ebony wings wider, eclipsing the sun and casting a shadow on us. He was beautiful, and he knew it. From the moment he stepped into the pond to the moment he claimed the sky. Sheen and I named him Jerry.

According to my roommate, Jerry is a cormorant. Or in Latin, a sea raven. They mainly live along either coastal or inland waters, including swamps, lagoons, and sometimes ponds. I guess Jerry saw the pond and thought it would be a good place to rest. But he was completely alone, and cormorants are known to stay in colonies, feeding off a family dynamic to survive. So where was Jerry’s family? Did he have one and he just decided to take a break from them like I did when I first started dorming? Did he lose them in his journey here and went looking in times of despair like I did this year? Did he go back to them after his little rest stop, or is he traveling to find a new home for a future family? Is the pond one of his considerations for a new home? We never saw Jerry again.

~~

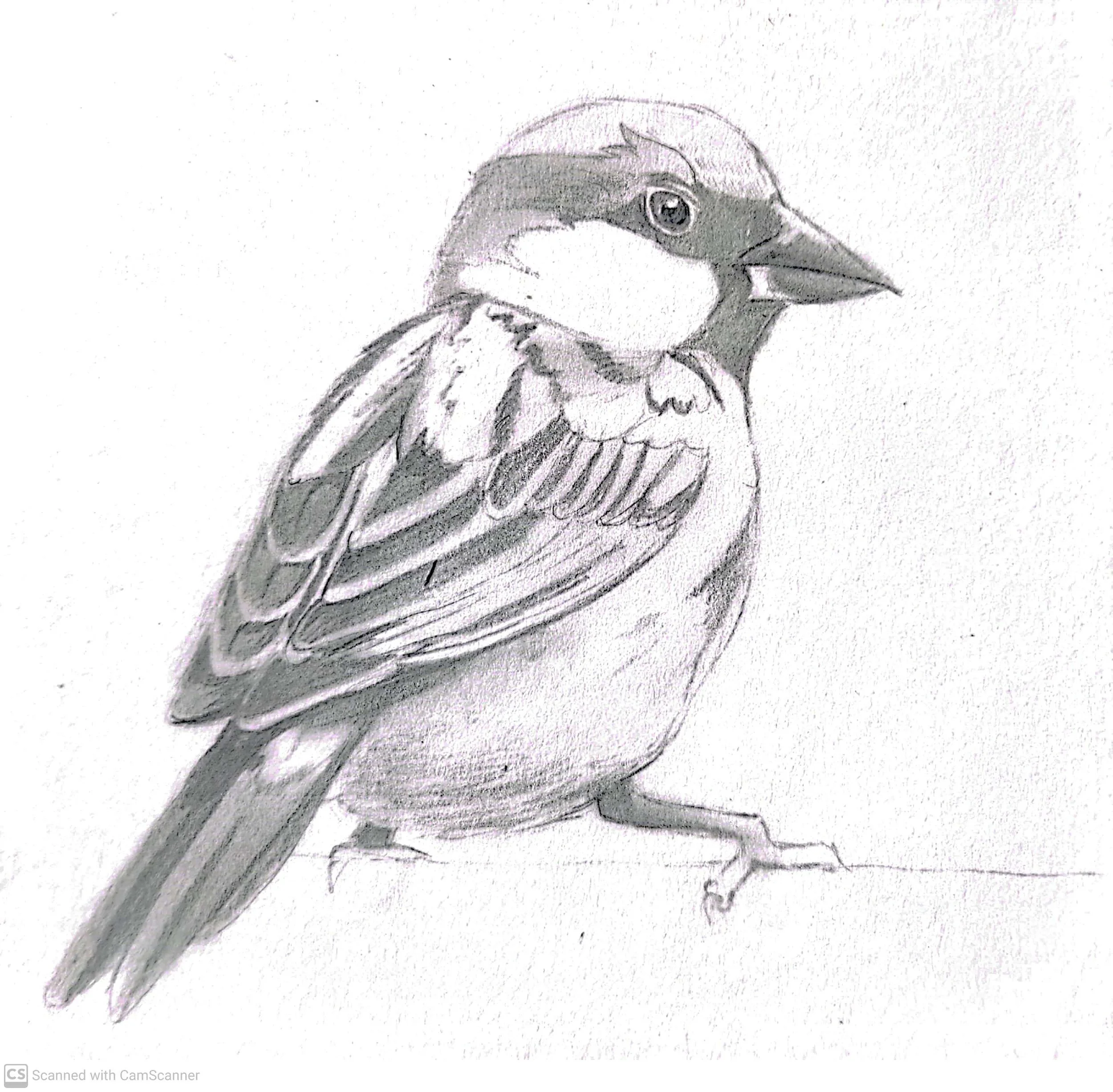

The house sparrow belongs to my first memory of this world. The small bird, which I remember my mom letting fly out the window off her hand when I first woke up, always perched low on the fences of homes or high in the neighborhood trees. However high they were able to reach at least. The males stand out with their bold, red-brown heads and wings the colors of a monarch butterfly. The females are more subtle, with their dull brown coats and feathers that for some reason remind me of sunflower seeds, both flying towards the sun as they grow. The females are at an advantage, being able to blend in better with the brown bark trees and hide in between their nests and leaves, as if they don’t exist, whereas males need their color to be chosen, to help carry a legacy. It’s a strange way to survive, with one disguised from the rest of the world, while the other needs to stand out to pass on. Despite their differences in living, they have one thing in common that makes it easy to know where they are:

Birdsong. Lyrics composed of bright, light chirps welcoming the sun that just begins to wake up. They are - were - especially loud in the spring and summer, when the house sparrows came home from their winter migration, seeking warmth and light. To meet old bonds and start new families - a beautiful way of life. A beautiful way to tell me the days are getting brighter, that it’ll be alright this year as long as their birdsong echoes through the trees every morning.

But what happens when you don’t hear their birdsong anymore? When it’s silent every morning, when the sun doesn’t shine as bright as it used to, the clouds cascading their dullness onto the world? It’s not even winter yet, so they shouldn’t have started their migration. That must mean they’re still here, right? But it’s been four years since I’ve heard their song. A song that doesn’t exist anymore when I go back home to the city every other weekend. Are they just hiding from the incoming dangers of the changing weather, or have they lost themselves on their way back home? Is it too cold to come back home? I assume so. I assume I have lost the birds of my childhood to the changing world where warmth is fleeting. But as I’m walking from the park back to my home, there I see a little brown bird, perched in the gaps of the black fence of my neighbor’s house. The house sparrow. My house sparrow.

Autumn is setting in, you should not be here. You should be in the skies with your brothers and sisters, flying South. And yet, I can’t bring myself to tell you to leave. I need you here.

Welcome home, my love.